One thing that has surprised me about this Substack gig, which I started 3 years ago, is the composition of my subscribers. I didn’t really have any expectation of a following when I started, I really did it for myself. Since then, I have accumulated a small following, and fewer still who are prepared to pay. Therefore, it has been a surprise to me that, of those who pay, there is a high proportion that are very experienced people. There are those who have worked in major Wall St. firms, owned their own hedge funds, or are currently active institutional portfolio managers. It strikes me that there is something about my work that only those who have enough professional experience and knowledge seem to recognize what they are seeing, but to others, I’m probably just another person making noise about markets and the economy … and in all likelihood with less personality … but more likely it’s because my work doesn’t look like everyone else’s and what people think market stuff is supposed to look like.

A couple of other examples of this phenomenon are:

A few years ago, I was visiting my doctor and he started quizzing me about financial markets once he found out what I did. He went on to say that he followed a particular person online (a person who has around 1 million followers), to which I said that this person followed me online … much to my doctor’s surprise.

This last week, I was sent a link to an news article citing John Hussman’s latest monthly publication. I said I had read it and sent them the link to the source article. I then mentioned that Dr Hussman had referenced my work a while back (he also follows me online) after I had shared an insight with him, which was sort of nice, especially because he produces his own work (I haven’t seen him reference another person’s work before). Again, more raised eyebrows.

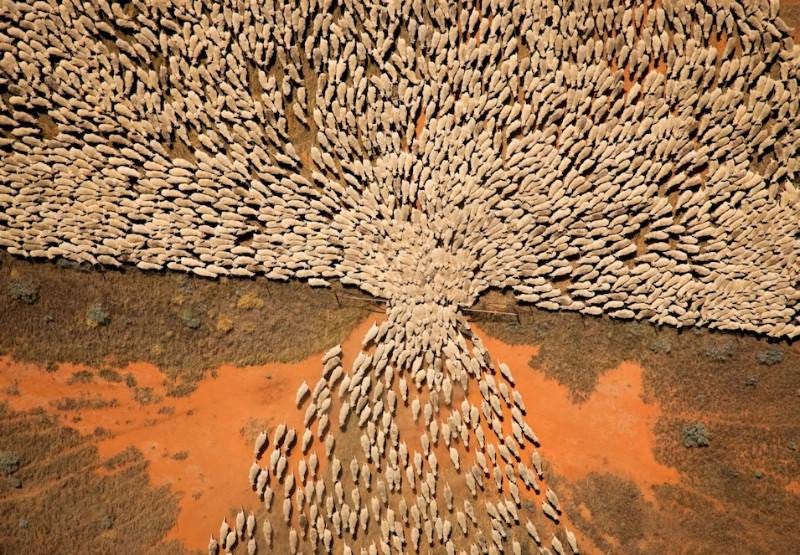

But enough preamble. One of my ‘long-time listener, first-time caller’ highly experienced, paying subscribers dropped an idea for my contemplation. The question was around liquidity, specifically market liquidity when everyone tries racing for the exit at the same time.

I had to do a bit of manual data gathering (i.e. entering hundreds of days of missing data in my datasets). Since AI has taken off, everyone realizes that data is valuable (i.e. they can sell it for training algorithms) and so there are now less data download sources and more paywalls. The internet made data freely available, but AI is taking it away. And before you respond, having tested AI, I don’t trust it to reproduce accurate data on demand, just the appearance of doing so.

Evacuate the dancefloor

So, back to the question posed by my roguish and debonair subscriber. A great question that has uncovered a really interesting market dynamic that has gone unnoticed.

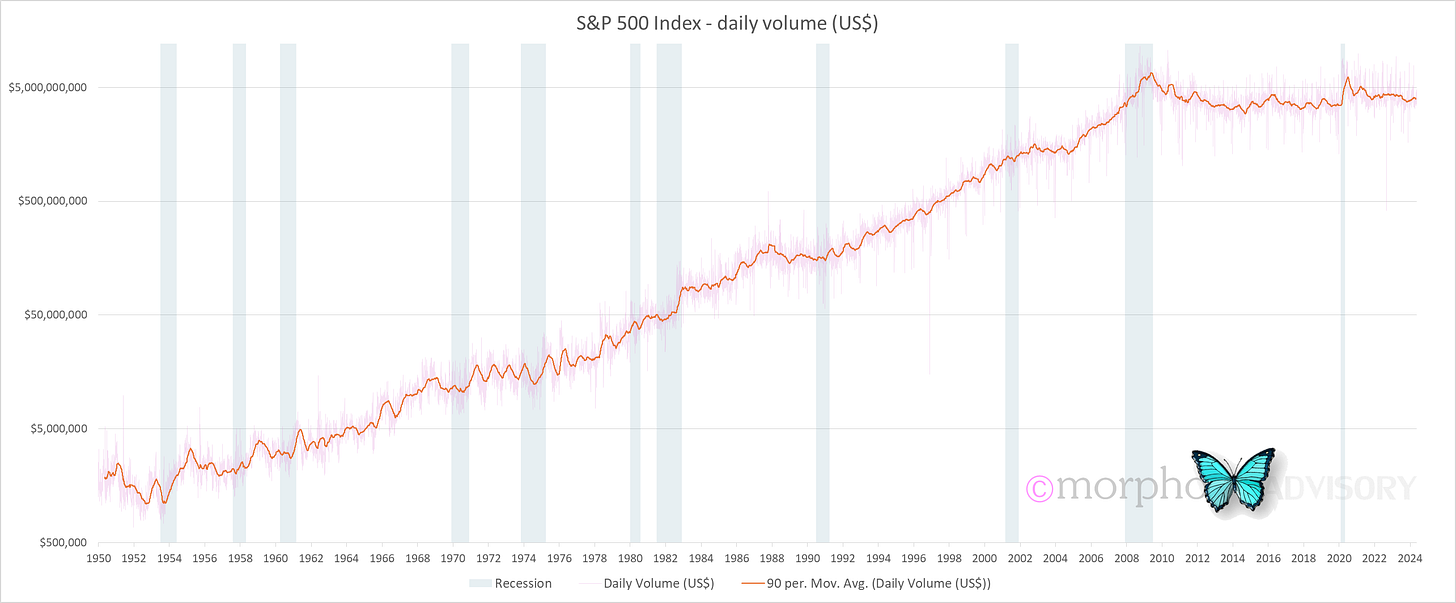

For 60 years from 1950, the daily volume traded in the S&P 500 (measured in dollar value) has risen fairly uniformly. This is intuitively obvious because as the market value rises (i.e. market capitalization) the value of trades should rise accordingly. But for the last 15 years, that historic uniformity of rising value of daily turnover stopped.

Did the value of the S&P 500 stop rising during the last 15 years? Not at all. The S&P 500 is approximately 7 times higher than it was at the low of the 2008 stock market crash.

For the last 15 years, the daily value traded has remained at a fairly constant US$4 billion +/-.

When we divide the price of the S&P 500 by the daily volume, we see the same fairly consistent trend from the 1950s to 2008. Because the trend is down, it means that the daily volume traded was rising faster than the price of the S&P 500. In other words, market liquidity was improving.

However, since 2008, market liquidity has been falling. This is due to the S&P 500 rising 7x while the daily turnover has remained unchanged.

But perhaps it’s not as bad as the above charts suggest. When I divide the daily value traded in the S&P 500 by total stock market capitalization, we see that the current turnover is a reversion to the levels seen from the 1970s to the 1990s.

Certainly, the above chart indicates that the market can increase its daily volume, having shown that it has done so in the past. However, it most notably does so at the backend of a market rout, when capitulation and panic set in. Have a look at the first chart at the top of this article and notice the acceleration in the moving average toward the end of the shaded recession periods (the log scale hides the magnitude, but the acceleration in trend is there).

Another factor to consider is the household exposure to stocks. It’s at an all-time-high, and its growth correlates to the doubling in household retirement assets since 2008.

That’s a problem.

There has been a rapid acceleration in aging population over the last decade, and these people are dependent upon their stock portfolio. Their entire quality of life in their sunset years is based upon the wealth they believe they currently have. Once they see that eroding rapidly they will end up in the same panicked capitulation selling (e.g. “I can’t take these growing losses anymore, I have to get out”) like we’ve seen at the tail-end of every market crash before.

It’s an unstable combination: a market that has flatlined in terms of its daily volume, and a rise in the number of people who will feel especially vulnerable in terms of their net worth and financial wellbeing during a down market.

I remind you of the extremes seen in Japan: A virtually crime-free society saw elderly women stealing small items so that they would be caught, arrested, and imprisoned. They did this just so that they would be housed and fed.

Boom-Bust, baby!

While I’m on the subject, let’s refresh our understanding on the unfolding shambles that sees the Fed trying to interpret a demographic cycle as a business cycle.

A primary reason for concerns about sticky inflation has been labor market dynamics. There has been a perceived shortage of workers over recent years, which has put pressure on businesses to pay higher wages to secure talent. Why has there been a labor shortage? Because more and more old people are leaving the workforce.