The seven year itch refers to the lifespan of relationships and their cycles, specifically the average period of happiness in a relationship. Economies also have cycles and they, too, experience happy times and endings.

I was contemplating the current economic cycle and came to the conclusion that the present environment feels pretty much likes things felt back in 2019. Economic activity was slowing, but not many people believed it back then either.

Of course, there are a few differences between now and 2019 (in the U.S.):

household debt is 25% higher;

federal debt is one-third higher;

corporate debt is over 25% higher;

the stock market is 100% higher;

house prices are 46% higher; and

interest rates are between 100% (bond yields) and 345% (Fed Funds) higher.

But, damn! These last 5-years we’ve had have been anything other than normal in economic terms. And all the wildness that happened in these last 5-years has been a distraction from the underlying situation. We’ve had:

the Covid shock that caused lockdowns

which caused the tech boom and zero interest rates,

which caused asset price speculation and the consumer shift of travel funds to capital goods,

and that caused supply chain problems and inflation,

which caused a rapid and severe rise in interest rates plus we also saw the unwind of the tech boom ….

And now we’re resuming our normal programming.

What’s normal about now? We’re back to just having tight monetary policy for an extended period and the effects that has on the economy.

Most importantly however, unnoticed and underneath it all – hidden by all the noise of the last 5-years, we have a massive demographic shift, which is more powerful than all the rest combined (though slower moving, like all inexorable forces).

The noise of the last 5 years has setup the Fed and other central banks to be distracted by short-term business cycle factors to the exclusion of tectonic economic shifts that their models ignore. They’re so confused in the current environment that they’re oblivious to the fact that all their policy tools won’t work against it. In the coming cycle, they’ll likely drop interest rates to zero (or below) and they’ll skyrocket QE like never before, but none of it will work against demographics. The economy needs to contract to the level of the population, just as it needed to expand to the level of the population when the bubble began in the 1960’s/70’s. But officialdom will do everything in their power to not let that happen and so, they will follow Japan’s failure example.

Anyhow, back to our current situation: the impact of tight monetary policy (i.e. high interest rates).

Tight monetary policy

One area where higher interest rates is most noticeable is in consumer credit. Credit card delinquency rates don’t look high when measured as a percentage of credit card customers, they’ve only gone from 2.6% in 2019 to 3.2% at present. However, that equates to an increase of $10bn p.a. in just interest payments – a 93% increase compared to 2019. The massive increase in credit card debt to all-time high levels (over $1.1 trillion) meets all-time high credit card interest rates (21.6%), and the highest proportion of people just paying the minimum balance (10.65% at the end of 2023 … data only goes back to 2013).

Yes, inflation needs to be brought down by monetary policy, but an element of inflation stickiness that central bankers are fighting is due to employers trying to replace their retiring workforce and finding it hard to do. Neither companies nor the Fed (and other central bankers around the world) realize that the difficulty in finding employees (a business operating cost) will also show up in a difficulty in finding new customers (business revenues). As such, the Fed’s record-breaking protracted tightening cycle is ensuring that the economy and markets will tip over into the void that awaits. And that’s about the only certainty that exists in markets & economics: policymakers will react and will break things.

We’ve had a massive 2-year influx of new participants in the economy that has veiled the financial pressures that households and businesses are under because of high interest rates, which is encouraging central banks to continue their restrictive policy.

Working-age population growth has a significant multiplier effect that makes it a greater force than interest rates - the only economic factor that can outweigh interest rates. But the 2-year jump in working-age population we’ve just experienced is a short-term one-off, unlike when the Baby Boomer and Millennial generations hit the economy in 1960/70s and 1990s, respectively.

Normal programming resumes

I’ve been pointing out for some time that unemployment will begin rising. Earlier today, it was reported that U.S. unemployment hit a new high in this cycle (4.1%). It’s now knocking on the door of the Sahm Rule (a recession indicator based on the change in the unemployment rate) and is well beyond Michael Kantrowitz’ similar rule-based threshold, suggesting the U.S. is in recession already.

The “soft-landing” that everyone is expecting and basing their forecasts on (and even making fun of those who said recession is coming) is looking increasingly unrealistic. #eggonface

So why would the stock market keep climbing if the economy is weakening?

Financial markets have a funny knack of being able to push people to their limit, when they can take no more financial pain and feel forced to capitulate, before finally doing what they’re “supposed” to do.

I came across the following quote a few days ago, which carries an air of truth ….

The above statement makes the following two headlines more understandable.

Mike Wilson of Morgan Stanley and Marko Kolanovic of JPMorgan - two of Wall St’s most talented strategists - have been feeling the pressure. Wilson has capitulated, while Kolanovic is “pursuing other opportunities”, which is corporate speak for being given the boot.

Wall St. is capitulating and either their staff capitulate also or there is a parting of ways. Wall St. is a sales business so strategists had better be right and right immediately if they’re suggesting a “don’t buy” strategy. The 2-year delay in the beginning of the recession and its accompanying bear market because of a transitory spike in working-age population is fucking with people’s heads.

The corporate world

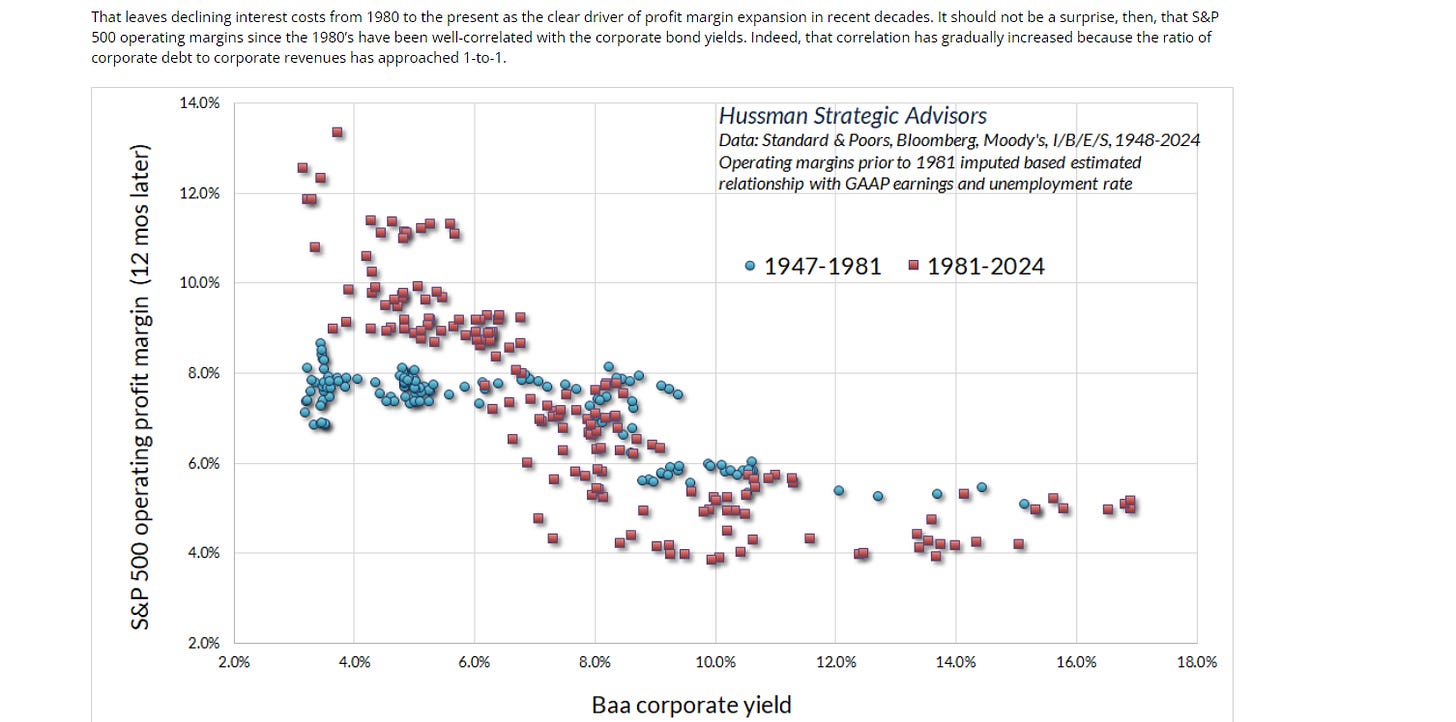

Speaking of corporate behavior, a comment in the latest monthly published by John Hussman Ph.D got me thinking. He attributes declining interest rates as the primary driver of corporate profit margin expansion over recent decades.

I have also long understood that the majority of corporate U.S. earnings growth, especially since the 1980’s, has been due to financial engineering and falling interest rates, and not so much a sales growth story.

I decided to have another look into it.

For as long as we have the data, U.S. corporate debt has been climbing relative to U.S. GDP. That corresponds with corporate earnings falling relative to debt (inverted trend).

In light of the above relationship, it’s unsurprising that corporate earnings have remained constant relative to GDP.

The greater amount of debt employed by corporations as capital (relative to equity) results in a greater return on equity, because debt is cheaper than equity. Financial engineering 101.

The use of debt has been climbing but interest rates have been falling faster, so basic financial engineering has delivered continued earnings growth.

However, each time interest costs rise - even only a little, corporates need to reduce other business costs to maintain their profit growth. Cost #1 is employees, so a recession follows because of rising layoffs.

The impact of the large rise in interest rates over the last 2-years have been held at bay by a 2-year spike in new customers, but there are no new customers in the pipeline anymore, so it’s back to cost-cutting, as can be seen by recently rising unemployment.

Interest rates delivered the gains in the stock market over recent decades, but things have got out of alignment over the last 2 years, with stocks running away.

The “Buffett Indicator” (i.e. the value of stocks relative to GDP) also suggests stock valuations are rich. I modified the Buffett Indicator because it’s quite simplistic. My adjustment normalizes the relationship between stocks and GDP by adjusting the Buffett Indicator for interest rates, which also suggests stock valuations over the last 2 years have been out of alignment.

The same yawning gap is waiting to be closed now that the population spurt is over.

I also applied this interest rate adjustment to another proprietary insight - my recent market breadth indicator.