There is so much information flying around that it’s easy to be hit from any direction.

I have seen multiple references to a market “melt-up”, which is when markets experience a sudden rise, and not just for a single trading session. Interestingly, two of the references were via global news agencies (Barron’s and the Financial Times) and the headlines were published in assertive terms, i.e. as though it was a certainty. Such headlines are often considered contrarian. But they do serve as a barometer of current market sentiment.

Additionally, there is talk from the Fed about achieving a soft landing now that interest rates are starting to come down, and snapshots of current economic data appear to indicate the economy’s resilience.

In the face of such prevailing sentiment combined with the narrative of institutions that possess the influence required to hold the headlines, it’s easy for our personal view to become overwhelmed.

In such circumstances, I like to step back and take stock.

Going back to first principles, I remind myself that there have only ever been three instances where a Fed tightening cycle (of which there have been 13, excluding the one that started in 2022) did not result in a recession. Firstly, this indicates the nature of our economy:

It is debt fueled - otherwise rising interest rates would have no impact; and

It also indicates that people live up to the limit of their means - otherwise they could absorb higher interest rates without a recession.

What were the conditions that caused those 3 instances of a soft landing? There were two:

Population growth, specifically working age population. A large growth in population is enough to provide systemic economic growth even as the debt-burdened portion of the populace struggle. The 2 instances of population growth that caused a soft landing were the Boomers in the late 1960’s and the Millennials in the mid-1990’s.

The only other soft landing was around 1984/85, and this was at a time when, immediately prior to the rate hike cycle, interest rates had recently fallen from around 20% p.a. and they had been rising for the 20 years prior to that. As such, borrowers were well conditioned to the fact that interest rates can, and do, rise, so they were prudent in terms of their debt levels and when it came to asset valuations.

In the current cycle (since 2022), borrowers have been conditioned to 40 years of falling interest rates, so they have become careless with debt levels and in regard to asset valuations. However, there has been significant population growth. This population growth, while a large and a sharp increase, has only been for a period of 2 years, so it is not generational in scale. Additionally, the growth rate (at best) only briefly touched the growth rate seen during the Generation X coming of age (which was generational in scale, so persisted for several years), and even that was not sufficient to prevent any economic hard landings. No, I am of the opinion that the current population growth is only sufficient to have temporarily deferred the inevitable (let’s call it “transitory”, shall we?), which has given the Fed confidence to prolong their tight monetary policy, resulting in the longest yield curve inversion in history.

On top of these ‘first principle’ musings, I remind myself that I employ a real-world dynamical system approach to interpreting economics, rather than the neoclassical academic theory. My approach is based around economic incentives and how they impact human behavior given prevailing circumstances. In short, the most predictable aspect of economics is human behavior. The specifics of each economic cycle may change, but humans remain predictably consistent.

Stepping away from the media’s prevailing sentiment articles and the speeches of the narrative influencers, what can we see in terms of the behavior of the collective?

Consumers are not as optimistic in terms of their outlook for income growth:

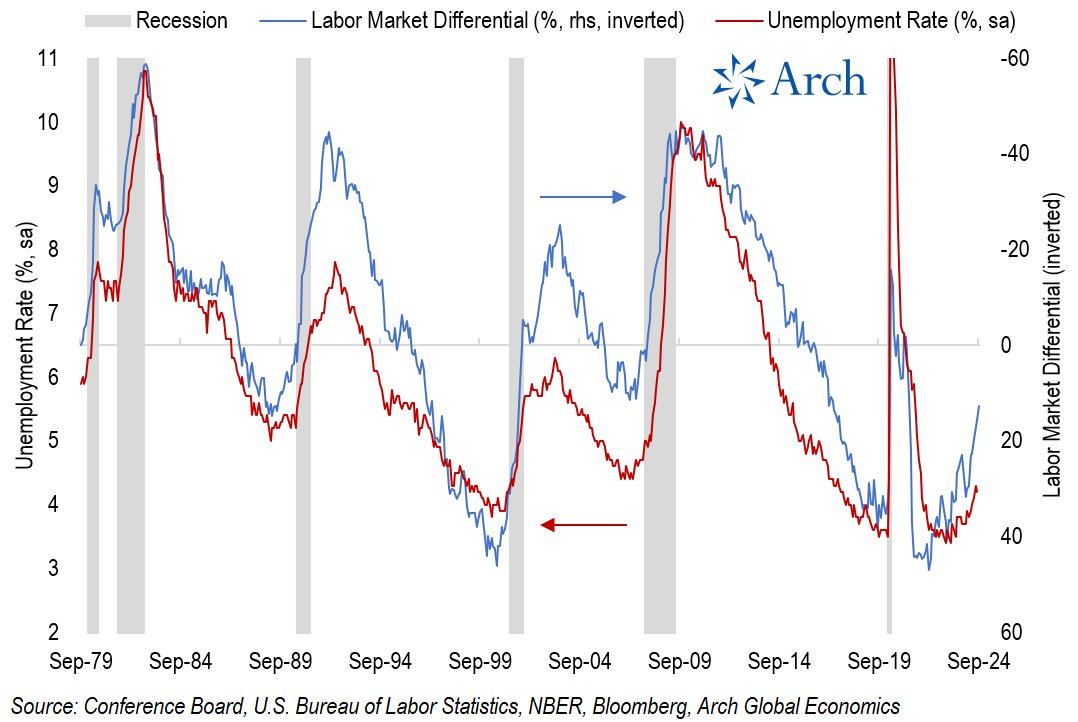

Nor are they as confident in their ability to find another job:

And that doesn’t bode well for the unemployment rate staying at low levels.

I had a deeper look into the consumer outlook for their income over the coming year and I found an interesting signal. It’s not just those who expect better or worse income growth, but the number of people who expect no change also tells us something.

There has been a large and persistent jump in the number of people who expect their income to stay the same over the coming year (inverted in the chart above). This defensive dose of realistic thinking has behavioral implications. It pulls back on the optimism that underpins free-spending behavior.

When income doesn’t look like growing, people look elsewhere. But as the Conference Board data in one of the charts above shows, jobs are becoming harder to find and less plentiful.

I had a look into some data on that front, too.

The Atlanta Fed produces wage tracker data that ordinarily shows that people make more money by switching jobs than by staying with the same organization. However, during tougher economic times, that situation reverses. When wage growth falls and “stayers” get more wage growth than “switchers”, that combination usually indicates a recession is in the offing.

Wage growth has been falling for the last 2 years, and the difference between switchers and stayers wage growth has just turned negative.

All in all, I would say that U.S. consumers (U.S. Households) are not in a happy place. In fact, the survey data suggests that their usual optimism has turned down quite sharply over recent months.

Nevertheless, investor bullishness continues unabated.

Looking at investor sentiment by measuring the rolling 3-year z-score from the AAII weekly survey, bullishness has been high for an extended period.

I decided to measure the number of days that this measure was positive and compare it to historical examples.

We are currently experiencing the 3rd longest run of bullishness of this measure on record. If there is a melt-up, we may already be in the midst of it.

I noticed that there was a 2-week period in mid-2023 where the score went briefly negative. The same thing happened in 2000. In fact, 1999-2000 and 2023-2024 are the two periods where there was an extended period of investor bullishness that wasn’t immediately after a major market crash. 2022 was only a market correction, much like 1998 was.

I’ve thought to myself before that the current market shares many similarities with the Dot-com period, and this adds to that view. Back then, the concept of valuation got tossed out, too.

So why are economic conditions still looking positive enough to encourage the Fed and others to think that a soft landing has been achieved? It’s a legacy issue.

The legacy of Covid-19 stimulus caused an economic boom. This happened just as Boomers were leaving the workforce en masse. Fortunately, a pre-GFC mini baby boom (and some sizeable immigration too, no doubt) brought in enough new labor (and their spending power) to sustain the windfall profits companies were making.

But the savings gained via stimulus and travel-free lockdowns has all been spent, not forgetting that inflation took a chunk of it. Companies are now seeing the outlook for their profit growth shrink. They’re cutting back on planned spending, withdrawing jobs that they were once looking to fill, as consumers slow their spending and marginal revenues become harder to find.

This creates a feedback loop onto consumers because jobs are no longer plentiful. Where there used to be 2 jobs for every available worker, now it’s back down to 1 … that is, if you’re in the right location and got the right skills …. and if they’re not ‘ghost jobs’ - a practice it seems many corporations engage in these days to create the impression they’re thriving (in tough times, keeping up appearances becomes even more important for those stock options) with no intention of ever filling these roles.

On top of the shrinking job offerings, the growth rate of the number of consumers has slowed once again and is itself threatening to turn negative.

I don’t care what the Fed says - it’s their job to inspire confidence, but it’s also their job to raise unemployment in order to curb inflation - things are not as rosy as they appear to be. When you lift the lid, there’s a smell that tells you something has gone off.

Did you guys see what happened in China last week? Reckon it will last? I don’t.

I also question the “melt-up” in the S&P 500. It’s possible we get another late-2017 leading into 2018, but ….

Still, perhaps this will be another similarity shared with 1999-2000?

Thanks for reading.